The History of Origami: From Washi to the World

Origami is one of those quiet wonders, a simple piece of paper that can turn into a bird, a flower, or a tiny creature with just a few folds. But behind each fold lies a story that began many centuries ago, long before the word “origami” even existed.

Let’s unfold that story together.

From Paper to Folding

Long before origami existed, paper itself had to be invented. It first appeared in China around the 2nd century BCE, replacing heavier writing materials like bamboo and wood. A few centuries later, papermaking techniques traveled through Korea and reached Japan.

The Japanese soon improved the process, creating soft, beautiful sheets that didn’t tear when folded. This was washi, Japanese handmade paper. It became an important part of everyday life and shaped much of Japan’s culture. From writing and wrapping to decoration and prayer, paper became more than just a material. It became a medium of expression.

Ceremonial Folding: The Beginning of Origami

At first, paper folding wasn’t done for fun. It was part of rituals. People wrapped offerings for the gods in folded paper, and those folds became more decorative over time. During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), noble families like the Ogasawara and Ise clans developed strict folding styles for ceremonies. These were called girei-ori, or ceremonial folds.

Some of these traditions are still alive today. The noshi envelope for gifts and the ocho-mecho butterflies used in weddings both trace their roots to these early ceremonial folds.

As time went on, folding slowly drifted away from rituals and became something people did simply for joy. Paper wasn’t just for writing or offering anymore. It was something you could play with, explore, and share.

Origami for Everyone

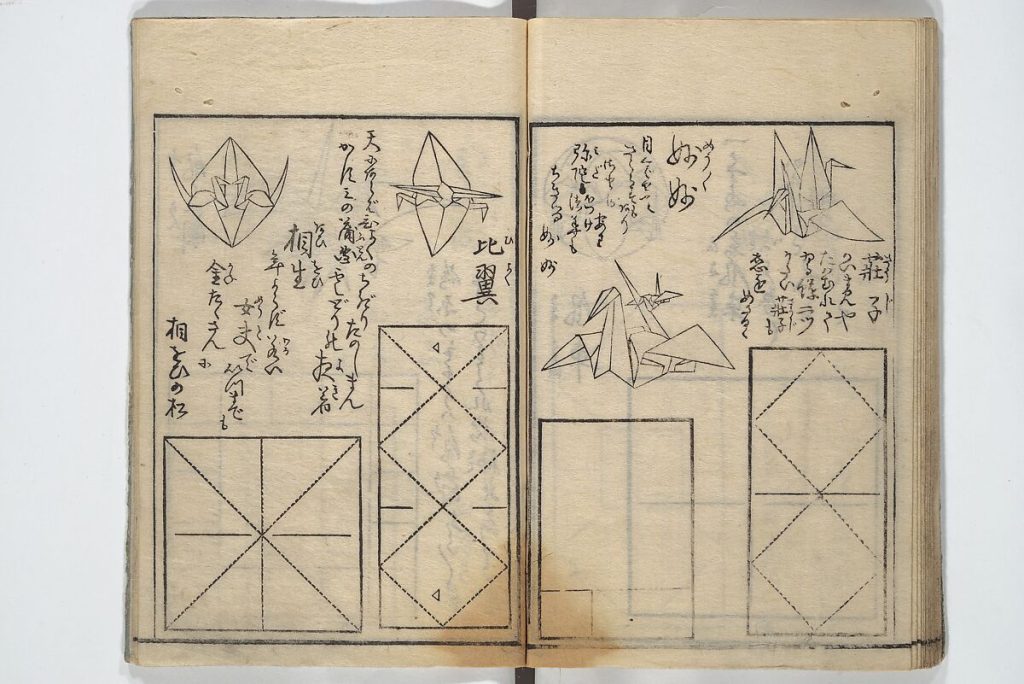

By the Edo period (1603–1867), paper had become affordable, and origami began to spread among common people. Scenes of folding even appeared in ukiyo-e prints, showing how popular it had become. Origami like cranes, samurai dolls, and decorative boxes were part of daily life.

In 1797, the oldest known origami book, Hiden Senbazuru Orikata (“Secret Folding Methods of a Thousand Cranes”), was published. It revealed just how deep the love for folding already ran in Japan.

Later, in the Meiji period (1868–1912), origami entered schools. Teachers used it in kindergartens and art classes to help children learn patience, balance, and precision. This new educational role helped origami grow even more.

Origami Goes Global

Early Paper Folding Around the World

While Japan refined the practice, paper folding appeared in other cultures too. In Europe, early drawings from the 1400s show folded boats and hats. By the early 1800s, folded paper animals, horses, and riders were found in German museum collections.

A big step came with Friedrich Fröbel, the German educator who created the first kindergarten. He used paper folding as one of his “occupations,” or creative lessons for children. This spread across Europe and eventually inspired Japanese educators during the Meiji era to include folding in their own classrooms.

The Modern Exchange

In the 20th century, Japan and Europe began to influence each other more directly. The Japanese origami crane (orizuru) made its way to the West, while European ideas about teaching and creativity helped shape origami in Japan. Slowly, all these traditions blended, and the word origami became the shared name for paper folding around the world.

Then came Akira Yoshizawa, often called the father of modern origami. Born in 1911, he transformed origami into an expressive art. He developed the modern system of folding symbols and traveled to more than 50 countries to share his work.

Yoshizawa’s ideas spread through an emerging network. In New York, Lillian Oppenheimer built the Origami Center and corresponded with Yoshizawa, while Samuel Randlett and Robert Harbin adopted and refined his notation into the Yoshizawa–Randlett system. Alice Gray edited The Origamian for years, and Robert Neale was part of Oppenheimer’s early circle. Together, this group helped turn origami into a global art and a bridge between cultures.

Modern Origami

Today, origami lives everywhere. There are artists who fold life-like animals, designers who use folding for fashion and architecture, and scientists who study folds for space and medical technology.

Japanese folders like Tomoko Fuse, famous for her colorful modular designs, and Makoto Yamaguchi, founder of Origami House and longtime supporter of young creators, continue to spread folding culture worldwide.

In the West, Robert J. Lang brought mathematics into origami, showing how geometry and computer models could help design folds once thought impossible. Nicolas Terry helped build a new publishing era by founding Origami-Shop, connecting artists around the world and making their diagrams widely available. John Montroll developed a systematic way of creating models from basic bases, inspiring a generation of designers to explore structure and logic in folding.

Nick Robinson, one of the most published origami authors, has shared his passion through dozens of books and decades of teaching, helping bring origami to classrooms, libraries, and families everywhere.

Other great names include David Brill, known for his elegant, expressive models; Satoshi Kamiya, whose detailed creatures set new standards for complexity; Eric Joisel, who turned origami into true sculpture with lifelike figures; and Giang Dinh, whose minimalist folds capture emotion with just a few curves.

Together, these artists — and many others — turned origami into a global creative movement, where tradition and innovation meet in every fold.

Origami has become a language without words, one that anyone can learn, no matter where they’re from.

At Origami.me, we’re proud to collaborate with many talented artists from around the world. You can explore their work here.

Why Origami Still Matters

The concept of origami is simple, but it holds something powerful. It teaches patience and care. It turns a flat sheet into something alive, just through our hands and imagination.

For some, folding is a peaceful way to slow down and focus. For others, it’s a way to create beauty or share joy. And for many, it’s a link to Japanese tradition that continues to evolve across generations.

Each time we fold a model designed by an artist, we share a quiet moment with them, following their thoughts, their choices, their rhythm. It’s a rare kind of connection, where creation is shared between two people through paper. In that way, origami becomes a form of participatory art, one where every folder helps bring an artist’s vision to life.

From ancient ceremonies to classrooms, from Japan to every corner of the world, origami keeps connecting people, one fold at a time.

Special thanks to Saki Maikuma for her help with research and translation from Japanese sources.

Sources

- History of Origami, Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun (Japan), pp. 1–6.

Covers the introduction of papermaking from China to Japan, the development of washi, ceremonial folding (girei-ori), the rise of everyday origami during the Edo period, the first printed origami book Hiden Senbazuru Orikata (1797), and modern artists such as Akira Yoshizawa, Tomoko Fuse, and Makoto Yamaguchi. - History of Origami, Hatori Koshiro

A detailed timeline of Japanese and European folding traditions, including girei-ori, early educational use, European paper folding, Friedrich Fröbel’s kindergarten system, and the merging of Japanese and Western traditions in the 20th century. - A History of Paperfolding, Origami Heaven by David Lister

- Comprehensive research on the global development of paper folding, including pre-modern traditions, Fröbel’s influence, and international exchange during the 20th century.

- History of Origami, Joseph Wu

Overview of origami’s cultural spread, historical documents, and major contributors, focusing on the Japanese educational system and 20th-century development. - British Origami Society archives

Articles on Akira Yoshizawa’s 1955 Amsterdam exhibition and the early international origami network (Oppenheimer, Randlett, Harbin, Neale, etc.), confirming the cross-cultural exchange that shaped modern origami. - Wikipedia and supporting biographies

Used to verify key details about Akira Yoshizawa, the Yoshizawa–Randlett notation system, Lillian Oppenheimer, Samuel Randlett, Alice Gray, and Robert Neale.